Understanding Deep-Sea Mining: Impossible Metals' Exploration Contract

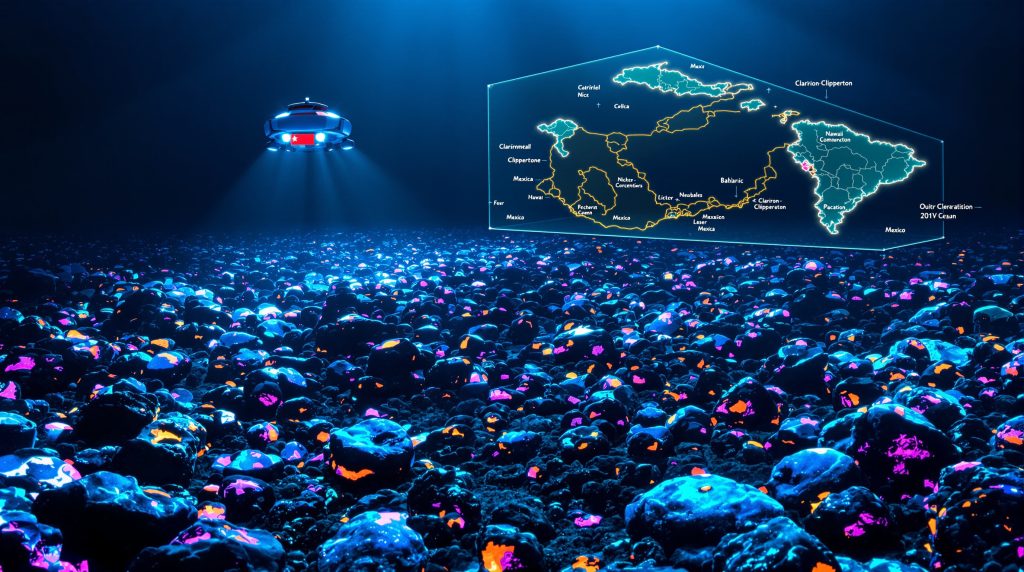

The Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ) represents one of the world's most significant deep-sea mineral resources, spanning approximately 4.5 million square kilometers across the Pacific Ocean between Hawaii and Mexico. This vast underwater region contains billions of polymetallic nodules—potato-sized rocks rich in critical minerals essential for renewable energy technologies and electronics.

These nodules, which took millions of years to form, contain concentrations of minerals crucial for the green energy transition. The typical composition includes 1.3-1.5% nickel, 0.2-0.25% cobalt, 1.1-1.3% copper, and 27-30% manganese—often exceeding concentration levels found in terrestrial mining operations.

The strategic importance of these resources cannot be overstated. Each electric vehicle requires between 30-60 kilograms of nickel and 5-20 kilograms of cobalt, depending on battery chemistry. As renewable energy adoption accelerates globally, securing sustainable sources of these critical minerals energy transition becomes increasingly vital.

These deep-sea nodules form at an extraordinarily slow rate—approximately 1-10 millimeters per million years—through the precipitation of metals from seawater around a nucleus such as a shark tooth or piece of sediment. Their potato-like size, typically 2-15 centimeters in diameter, makes them relatively easy to collect compared to traditional hard-rock mining operations.

How Does the International Seabed Authority Regulate Deep-Sea Mining?

The International Seabed Authority (ISA), established under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, serves as the governing body for all mineral-related activities in international waters. Its dual mandate includes developing regulations for deep-sea mining and ensuring environmental protection of marine ecosystems.

The ISA's governance structure consists of three main organs: the Assembly (supreme organ comprising all member states), the Council (executive organ with 36 elected members), and the Secretariat (headed by Secretary-General Leticia Carvalho). The Legal and Technical Commission, a subsidiary body of 30 expert members, examines exploration applications and provides technical advice.

The ISA operates through a unique system that includes:

-

Reserved areas: Sections of the seabed set aside specifically for developing nations or their sponsored entities

-

Exploration contracts: 15-year agreements allowing detailed study but not commercial extraction

-

Environmental safeguards: Requirements for baseline studies and impact assessments

-

Legal and Technical Commission: Expert body that evaluates applications

Currently, the ISA has granted 21 exploration contracts to various countries, with commercial mining regulations still under development. Each exploration contract covers areas up to 75,000 square kilometers for polymetallic nodules, though contractors must relinquish portions of their allocated areas during the contract period.

The ISA's Mining Code establishes comprehensive regulations for prospecting and exploration activities, including environmental protection measures. Contractors must conduct detailed baseline environmental studies before any activities commence and develop environmental management plans that demonstrate how potential impacts will be mitigated.

What Makes Impossible Metals' Application Significant?

Bahrain's Historic Sponsorship

Impossible Metals' application, backed by the Kingdom of Bahrain, marks a significant milestone as the first West Asian and Arab country to sponsor deep-sea mining exploration. This partnership reflects:

-

Expanding geographical diversity in deep-sea mining interests

-

Strategic economic diversification for Bahrain beyond traditional petroleum resources

-

Growing recognition of critical minerals' importance in future energy systems

This historic sponsorship aligns with Bahrain's Vision 2030 economic diversification strategy, which aims to reduce dependence on oil revenues and develop new sectors of economic activity. By participating in deep-sea mining exploration, Bahrain positions itself as a pioneering player in the emerging critical minerals sector.

ISA Secretary-General Leticia Carvalho highlighted this development as demonstrating "the universality, legitimacy and functionality of the ISA's unique system," while emphasizing the region's "strong commitment to multilateralism and the advancement of deep-ocean marine scientific research."

Technical and Environmental Approach

Impossible Metals' exploration application includes several distinctive elements:

-

Six designated exploration blocks within the ISA's reserved acreage

-

Comprehensive environmental assessment plans using advanced autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV) technology

-

Innovative technological approaches to minimize ecosystem impacts

The company positions itself at the intersection of economic opportunity and environmental responsibility, with CEO Oliver Gunasekara stating that Impossible Metals is "proving that innovation can unite economic value with environmental responsibility" while "pioneering a new approach to sourcing the critical minerals essential for clean energy and global security."

This balanced approach reflects growing industry recognition that environmental stewardship must be integrated into resource extraction activities, particularly in sensitive deep-sea environments.

What Are the Environmental Considerations for Deep-Sea Mining?

Ecosystem Concerns

Deep-sea mining presents unique environmental challenges that require careful consideration:

-

The CCZ hosts diverse and largely understudied marine ecosystems with over 5,000 identified species

-

Approximately 80-90% of CCZ species are new to science and potentially endemic to the region

-

Sediment plumes from mining operations could affect water column ecosystems and travel hundreds of kilometers

-

Recovery rates for deep-sea environments are typically very slow, ranging from decades to centuries

The benthic communities associated with polymetallic nodules demonstrate remarkable biodiversity. Nodules serve as hard substrate habitats in an otherwise soft sediment environment, supporting diverse communities of sessile organisms including sponges, cnidarians, and bryozoans. Their three-dimensional structure creates microhabitats that support higher species diversity than surrounding sediment areas.

Environmental Protection Frameworks

The ISA requires extensive environmental safeguards as part of its regulatory approach:

-

Baseline environmental studies before any activities begin

-

Environmental impact assessments for all operations

-

Reserved "no-mining" areas to preserve representative ecosystems

-

Nine Areas of Particular Environmental Interest (APEIs) covering approximately 1.44 million square kilometers

-

Ongoing monitoring throughout exploration activities

Noise pollution from mining operations represents an additional environmental concern that has received increasing scientific attention. Deep-sea environments are typically characterized by very low ambient noise levels, and the introduction of mining equipment could significantly alter acoustic environments, potentially affecting marine mammals, fish, and invertebrates that rely on acoustic communication.

How Does the Reserved Area System Work?

The ISA's reserved area system represents a unique approach to ensuring equitable access to seabed resources:

-

When developed nations apply for exploration rights, they must identify two mining sites of equal estimated commercial value

-

The ISA selects one site for the applicant and reserves the other for developing nations

-

These reserved areas form a "site bank" managed by the ISA

-

Developing nations can then apply for exploration rights in these reserved areas

This innovative system has created a substantial "site bank" of approximately 750,000 square kilometers within the Clarion-Clipperton Zone, representing roughly half of all areas for which exploration applications have been submitted. These reserved areas contain similar nodule densities and mineral compositions to areas already under exploration contracts, ensuring their equivalent commercial value.

Impossible Metals' application targets six blocks within this reserved acreage, demonstrating how the system functions to provide opportunities for diverse participation in deep-sea mineral exploration. This approach reflects the principle that the seabed is "the common heritage of mankind" and ensures that developing countries retain access to these resources even as technological capabilities and economic conditions evolve over time.

What Technology Is Being Developed for Deep-Sea Mining?

The technological challenges of operating at depths of 4,000-6,000 meters have driven significant innovation in the deep‐sea mining companies sector:

-

Remote operated vehicles (ROVs) capable of withstanding extreme pressure

-

Autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) for mapping and surveying benthic ecosystems

-

Nodule collection systems designed to minimize environmental disturbance

-

Real-time environmental monitoring technologies to assess operational impacts

-

Specialized surface vessels for processing and transporting collected materials

Companies like Impossible Metals are developing systems that aim to balance efficient resource recovery with environmental protection. The extreme operating environment—characterized by pressures exceeding 400-600 atmospheres, near-freezing temperatures, and complete darkness—necessitates specialized engineering solutions not required in conventional mining operations.

Recent technological advances in underwater robotics, particularly in autonomy and artificial intelligence, have significantly improved the feasibility of deep-sea mining operations. Modern AUVs can conduct detailed seafloor mapping at resolutions of 10-25 centimeters, enabling precise identification of nodule fields and environmentally sensitive areas that should be avoided during collection activities.

What Is the Timeline for Deep-Sea Mining Development?

The path from exploration to potential commercial mining involves several distinct phases:

-

Application review (current stage for Impossible Metals): The ISA's Legal and Technical Commission evaluates the technical and environmental aspects of the proposal

-

Exploration contract approval: If approved, a 15-year exploration contract would be granted

-

Exploration activities: Detailed mapping, sampling, and environmental studies

-

Environmental impact assessment: Comprehensive analysis of potential ecosystem effects

-

Mining regulations finalization: The ISA continues developing the regulatory framework for commercial operations

-

Exploitation contract application: Following exploration, companies may apply for commercial mining rights

The ISA has not yet finalized its regulations for commercial mining, making the timeline for potential production uncertain. Most industry observers expect commercial deep-sea mining operations remain several years away at minimum, with the earliest possible commercial production unlikely before 2028-2030.

The development of exploitation regulations has been ongoing since 2014, with multiple draft versions circulated and discussed among stakeholders. These regulations must address complex issues including environmental standards, benefit-sharing mechanisms, financial arrangements, and technology transfer requirements—all subjects of intensive negotiation among ISA member states.

What Are the Geopolitical Implications of Deep-Sea Mining?

The race to secure critical mineral resources from the seabed has significant geopolitical dimensions:

-

Supply chain security: Nations seek to reduce dependency on concentrated mineral sources

-

Critical mineral access: Essential components for clean energy and defense technologies

-

Technology leadership: Countries and companies compete to develop advanced deep-sea capabilities

-

Environmental governance: International cooperation on ocean resource management

-

Economic development: Potential opportunities for developing nations through the ISA's equitable access system

Current terrestrial sources of critical minerals are heavily concentrated in specific regions. Approximately 70% of global cobalt production comes from the Democratic Republic of Congo, creating significant supply chain vulnerabilities. Similarly, nickel production is dominated by Indonesia and the Philippines, while copper mining is concentrated in Chile, Peru, and China.

Bahrain's sponsorship of Impossible Metals reflects these broader geopolitical considerations, positioning the kingdom as a participant in the emerging critical minerals landscape. This move aligns with regional trends toward renewable energy and clean technology industries—a significant shift for a region historically associated with fossil fuel production.

The ISA's governance model represents a unique experiment in international resource management, with both developed and developing nations having stakes in the evolution of deep-sea mining regulations. The outcome of ongoing negotiations over exploitation regulations will have far-reaching implications for global mineral supply chains and the distribution of benefits from seabed resources.

How Does Deep-Sea Mining Compare to Land-Based Mining?

Deep-sea mining offers both potential advantages and challenges compared to traditional land-based mining:

| Aspect | Deep-Sea Mining | Land-Based Mining |

|---|---|---|

| Mineral concentration | Often higher grade deposits (1.3-1.5% Ni, 0.2-0.25% Co) | Increasingly lower grades requiring more processing |

| Land disturbance | No deforestation or displacement | Can require significant land clearing and community impacts |

| Infrastructure needs | Specialized vessels but no permanent facilities | Roads, processing plants, tailings dams, etc. |

| Energy requirements | High energy for deep-sea operations | Increasing energy needs as ore grades decline |

| Waste management | Challenges with sediment plumes | Tailings dams and acid mine drainage concerns |

| Ecosystem knowledge | Limited understanding of deep-sea ecosystems | Better understood terrestrial impacts |

| Regulatory framework | Still developing under ISA | Well-established but varying by jurisdiction |

This comparison highlights the complex trade-offs involved in mineral sourcing decisions. Land-based mining operations typically involve extensive physical disturbance, including deforestation, open-pit excavation, and waste rock disposal. These activities can lead to habitat destruction, soil erosion, and potential contamination of surface and groundwater resources.

In contrast, deep-sea mining targets nodules lying freely on the seafloor, potentially reducing the physical disturbance footprint compared to terrestrial operations. However, the creation of sediment plumes and disturbance of previously undisturbed benthic ecosystems present different environmental challenges that require careful management and ongoing research.

The processing requirements for polymetallic nodules are generally less intensive than those for terrestrial ores, which often contain lower concentrations of target metals and require energy-intensive crushing, grinding, and chemical processing. This difference could potentially reduce the overall environmental footprint of metal production from deep-sea sources.

FAQ: Deep-Sea Mining Exploration

What are polymetallic nodules?

Polymetallic nodules are rock-like formations that form over millions of years on the seabed, containing concentrated deposits of multiple metals including nickel, cobalt, manganese, and copper. They typically range from 1-15 cm in diameter and lie on the ocean floor at depths of 4,000-6,000 meters. Their formation process is extraordinarily slow, with growth rates of approximately 1-10 millimeters per million years through the precipitation of metals from seawater around a nucleus.

Why is deep-sea mining controversial?

Deep‐sea mining controversy remains primarily due to concerns about potential impacts on poorly understood marine ecosystems, questions about the effectiveness of environmental protections, and debates about whether alternative approaches to meeting mineral demand should be prioritized. The CCZ hosts over 5,000 identified species, with approximately 80-90% new to science and potentially endemic to the region. Recovery rates for deep-sea environments typically range from decades to centuries, making any disturbance potentially long-lasting.

How many countries have exploration contracts in the CCZ?

Currently, 21 countries have been granted exploration contracts by the ISA for various parts of the CCZ, representing a diverse range of developed and developing nations. These contracts grant exclusive rights to explore designated areas for 15-year periods, with possibilities for extensions under specific circumstances.

Is commercial deep-sea mining currently happening?

No commercial deep-sea mining is currently taking place in international waters. All existing contracts are for exploration only, with regulations for commercial exploitation still under development by the ISA. The earliest possible commercial production is unlikely before 2028-2030, pending finalization of exploitation regulations and completion of exploration activities.

What role do developing nations play in deep-sea mining?

The ISA's system specifically reserves areas for developing nations or entities sponsored by them, ensuring equitable access to seabed resources. This approach aims to prevent technological advantages from giving developed nations exclusive control over these resources. Approximately 750,000 square kilometers within the CCZ are currently reserved for developing countries, representing roughly half of all areas for which exploration applications have been submitted.

Ready to Capitalise on Major Mineral Discoveries?

Don't miss the next major ASX mineral discovery—Discovery Alert's proprietary Discovery IQ model delivers instant notifications on significant announcements, converting complex data into actionable investment opportunities. Explore historic returns from major discoveries and start your 30-day free trial at Discovery Alert's discoveries page.